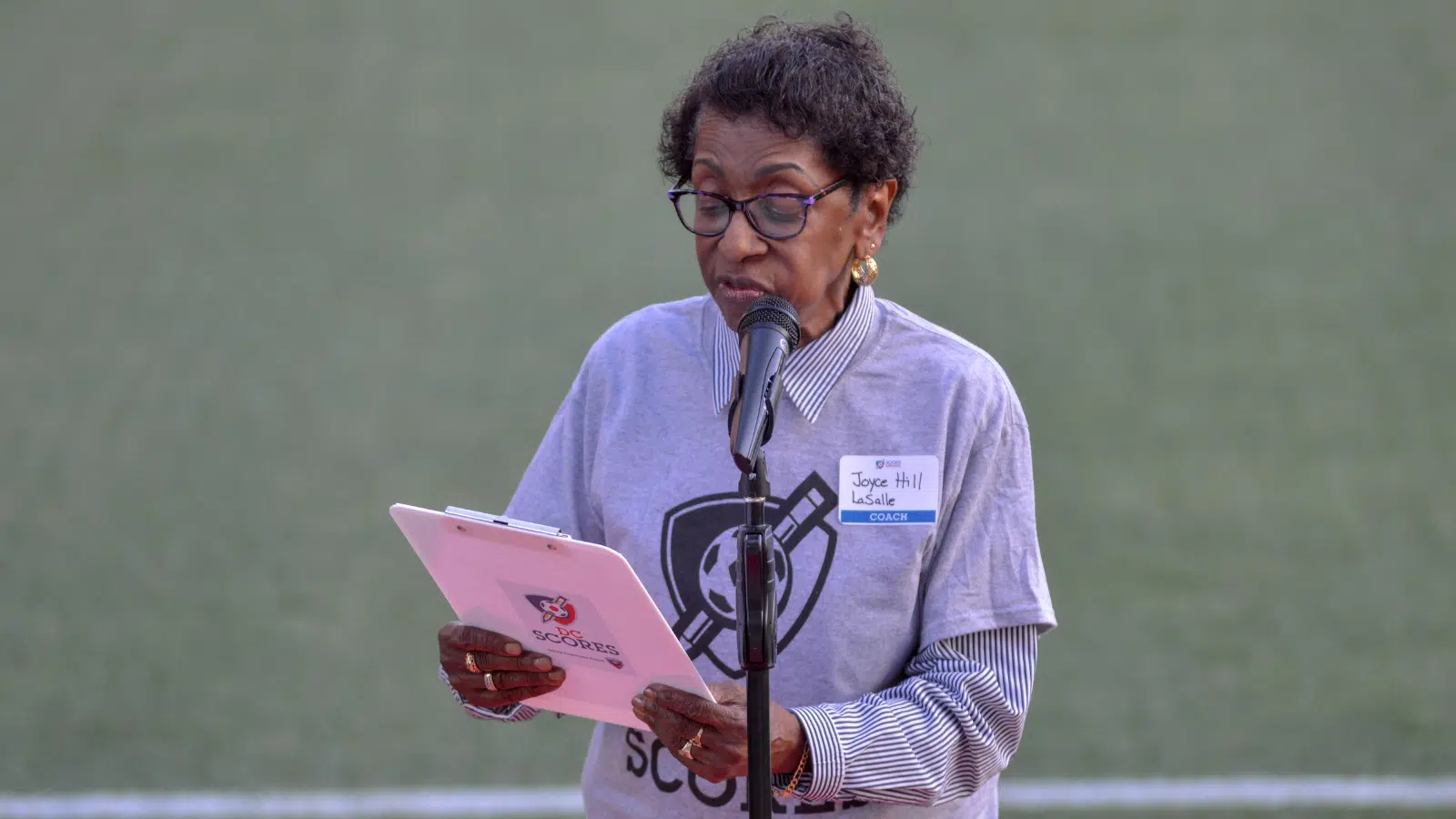

“I Was Part of History”: DC SCORES Coach Joyce Hill Shares Her Experience of the Civil Rights Movement With a New Generation of Poet-Athletes

When students at LaSalle-Backus Elementary School learn about the civil rights movement, they have the privilege of hearing its history from someone who was there.

Throughout her 25 years as a DC public school teacher, Joyce Hill, a first-grade teacher and DC SCORES poetry coach at LaSalle-Backus, has shared her experience of some of the most important moments in American history with her students. She grew up during the civil rights era and began volunteering for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in high school. Before she had even begun college, she had met Dr. Martin Luther King and attended the 1963 March on Washington.

“Now, the students look at me like they’ve discovered a fossil from the dinosaurs!” she jokes.

However, she continues, their realization that the civil rights movement, and the abuses it fought against, occurred in living memory is a powerful lesson for her students. Hill says her personal story emphasizes how recently the movement’s victories were won and the role a new generation of young people must play in ensuring that they endure. “If you don’t know your history, you’re gonna repeat it,” she warns.

“You Felt That Camaraderie”

Born in Yonkers, New York, Hill moved to Montgomery County, Maryland — which borders the District of Columbia — when she was three years old. Segregation laws had not yet been struck down and Hill and her family were frequently subjected to racism by their white neighbors.

From first through seventh grade, Hill attended segregated, all-Black schools. In eighth grade, her mom sent her to an integrated school in Yonkers for a year. “She got tired of the situation in Montgomery Country,” Hill says. When Hill returned to Montgomery County for ninth grade, the county had just completed integration in its schools.

“The whites there didn’t want us,” she says, remembering her experience in one of the first cohorts of Black students to join the school. “They would be across the street shouting, ‘2, 4, 6, 8! We don’t want to integrate!’ And when we got on the bus, they called us ugly things. It was very, very, very difficult.”

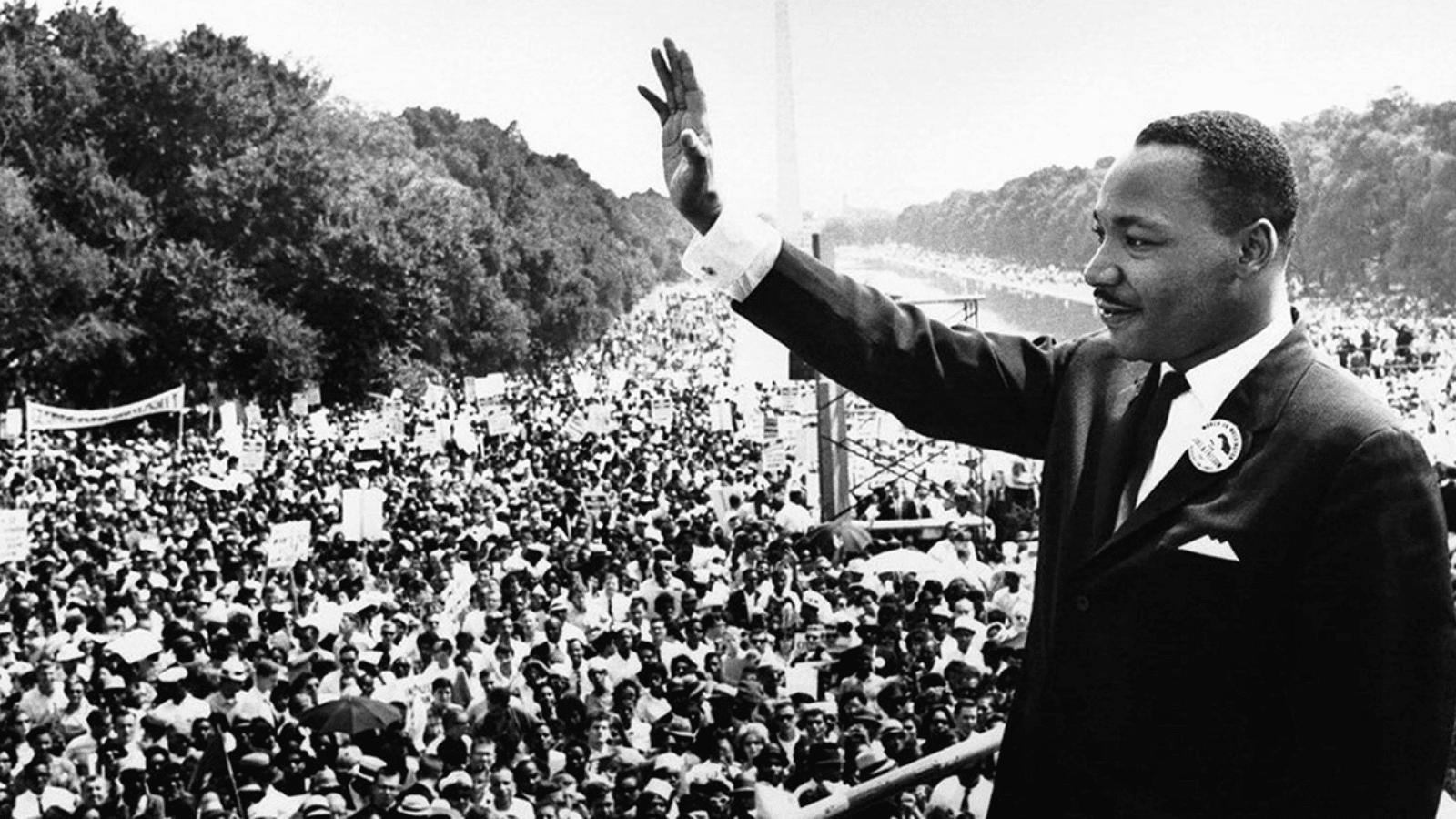

Hill attended the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Dr. Martin Luther King gave his historic “I Have a Dream” speech.

During these high school years, Hill began to get involved with local civil rights organizations. She and a friend spent their weekends stuffing envelopes in the office of Edith Throckmorton, who was the president of the Montgomery County Chapter of the NAACP. When Dr. Martin Luther King gave a speech to the chapter, Hill was in the audience and even got his signature. “He wasn’t as famous yet,” she recalls. “But, then again, he was to us.”

Years later, Hill would encounter King again during the March on Washington. With members of her church congregation, she took a bus to DC for what would be one of the largest political rallies in U.S. history.

It was a hot day, and Hill dipped her feet in the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool to cool off. She remembers the atmosphere as festive, with marchers in her group connecting over fried chicken, potato salad, and Kool-Aid while the speakers delivered their addresses.

“And then I remember a thunderous crowd and we knew Dr. King had arrived,” she says. “You felt that camaraderie,” she continues “I did not know how important that was until later when I knew I was part of a piece of history.”

Teaching a History Under Threat

The March on Washington had a transformative effect on Black communities in the DMV, says Hill. “It changed things because we saw that we could come together and show people what we wanted,” she stresses.

But the impact of white supremacy lingers, too. A few years ago, Hill was invited to attend her high school class’s 60th reunion. She and the majority of her Black classmates refused to attend. “We didn’t want to go,” she says. “Our white classmates talking about ‘Oh, we went to this shop and that place.’ We never went to the soda shop! We don’t remember that because we weren’t allowed to eat at those shops.”

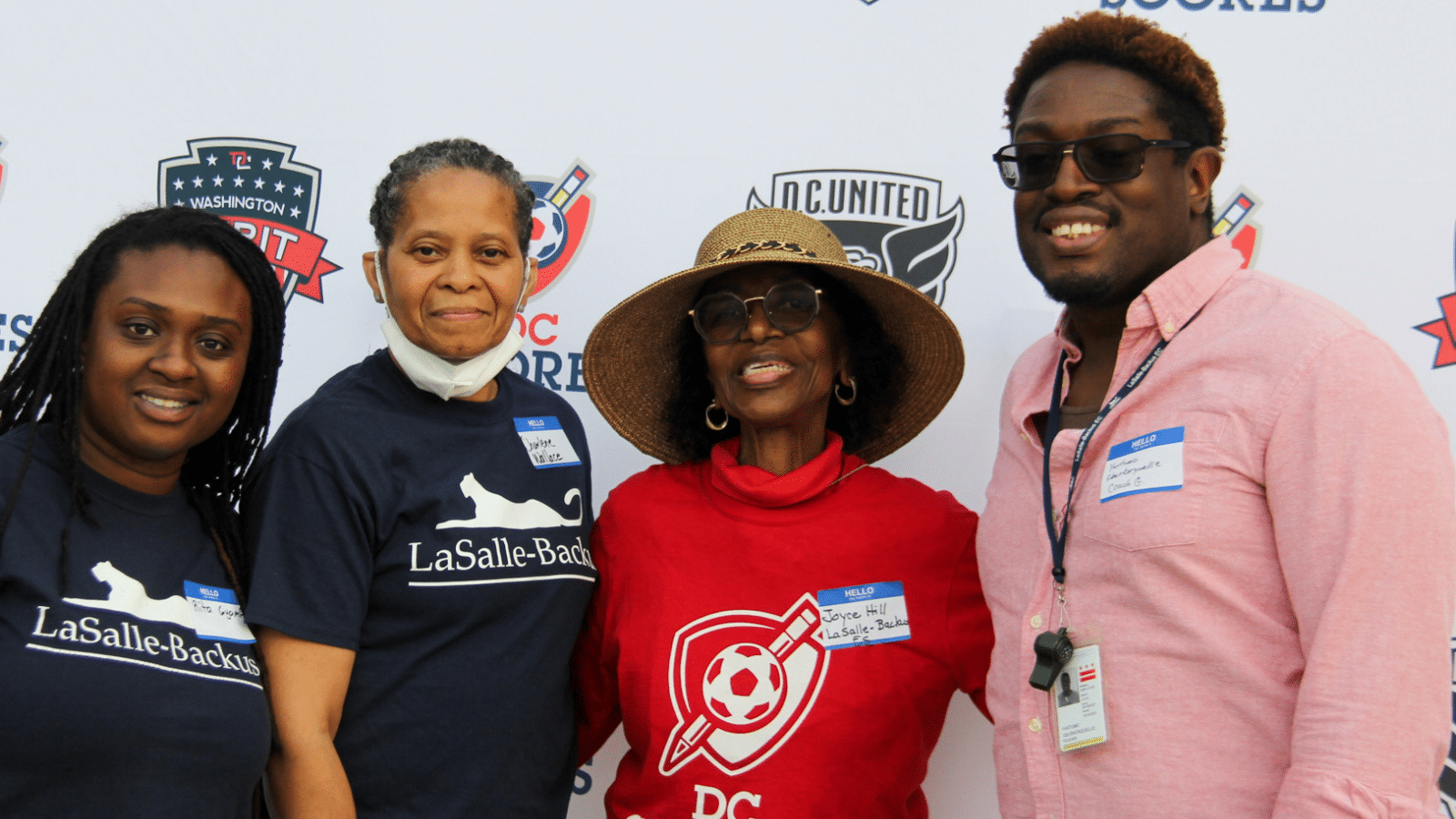

Hill (center right) attends SCORES Awards with her fellow DC SCORES coaches and teachers at LaSalle-Backus.

While the events that Hill lived through continue to reverberate today, the teaching of both Black history and the history of race in the United States is under threat across the country by politicians and campaigners who want to prohibit these lessons as part of a broader attack on what is often erroneously described as “critical race theory.”

Educators, civil rights campaigners, and Black parent groups insist that the attack on critical race theory, a concept that originated in law schools to describe the institutionalization of racism in American society and which is not generally taught in grade school, is little more than a veiled effort to erase Black history from children’s classrooms. That, says Hill, is exceptionally dangerous.

“All that stuff about critical race theory is rubbing me the wrong way. How can you not teach this history?” she asks. “If they don’t teach it, history will repeat itself. And some of these kids will have no knowledge of what their ancestors went through.”

With Black history under attack, Hill believes it is even more imperative to conserve the stories and experiences of the DMV’s African-American communities, a practice she leads for her students in DC SCORES writing sessions.

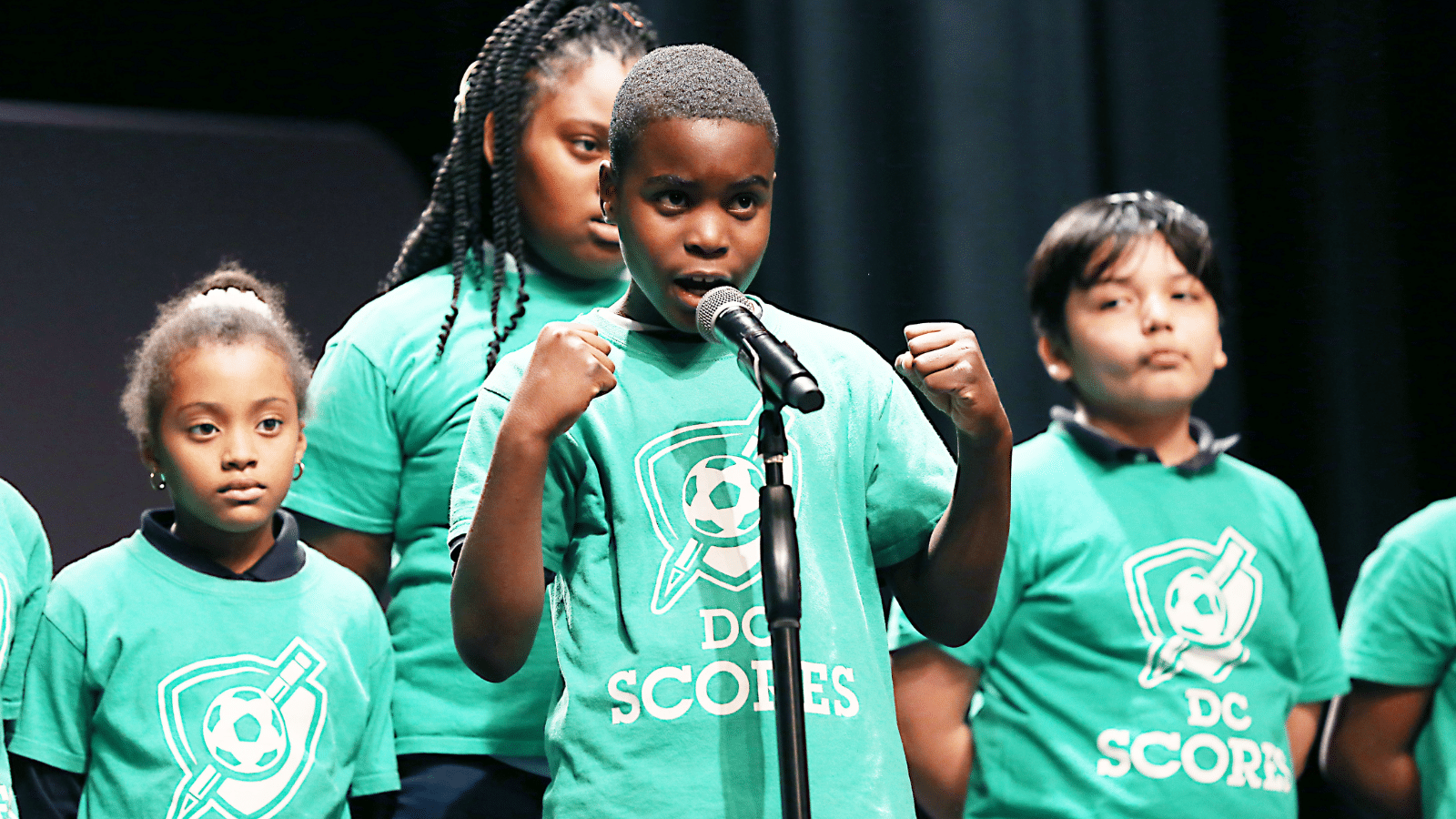

Hill joins the LaSalle-Backus coaching team and Washington Spirit and D.C. United players on-stage after the school won second place in the 2022 Westside Poetry Slam.

“I Love DC SCORES”

For more than a decade, Hill has begun her DC SCORES writing curriculum by inviting poet-athletes to share the issues in their neighborhoods that they most want to explore through their poetry. “We usually have ten or twelve topics, and then the students vote on it,” she explains. “We coaches don’t tell the kids what to write about, we just cue them to bring up topics.”

In the fall 2022 season, the LaSalle-Backus team collectively wrote and performed pieces addressing child abuse and challenging home environments, as well as a poem about Kyla Thurston, a DC resident who was violently pushed off a Metrobus by a group of teens last year.

The process was cathartic for her students. “The kids’ anger came out and they wrote down some heavy-duty points,” says Hill. “They wrote about their anger and put it into poetry form.” And, while the workshops provide space for poet-athletes to confront challenging or painful topics, they also create a community where students can support one another.

A LaSalle-Backus poet-athlete performs at the 2019 Westside Slam.

Hill shares the experience of one of her poet-athletes whose family was dealing with housing insecurity. The turbulence outside of school made it difficult for the student to attend practices. He was, however, able to write a poem, which he asked Hill to share with the DC SCORES team. “He made it to the slam and the team performed his poem,” she shares. “Afterwards, the whole team hugged him. He was so proud .”

Hill’s belief in the DC SCORES program to create positive experiences for her students also extends beyond the poetry classroom. Last season, she coached soccer for the girls’ team when a vacancy came up for the semester. “I said, ‘I don’t know anything about soccer but yes, I can do it.’ So I read up on the game and I took the girls out on the field,” she says. “We, as coaches, have to be teammates,” she adds. “It’s got to be both poetry and soccer.”

And though Hill is about to celebrate her fifteenth year with DC SCORES, she has no intention of retiring from the organization any time soon. “I take my hat off to DC SCORES,” she says. “I love it.”