“Poetry Is My Foundation”: How Alumna Zarea Boyde Found Her Voice, and Her Power, Through DC SCORES

Zarea Boyde can pinpoint the exact moment she knew she was hooked on DC SCORES.

She was seven years old, wearing a SCORES jersey that went down to her knees, and her sister, Zitiya, had just scored a sublime goal. Boyde was still celebrating when their opponents kicked off and passed the ball to a midfielder who rocketed it into her stomach.

“Yeah, I hit my knees,” Boyde remembers. “It wasn’t even a feeling of embarrassment, it was a feeling of, like, ‘Okay, we gotta get better because this is definitely not happening again.’ That’s what made me take soccer serious.”

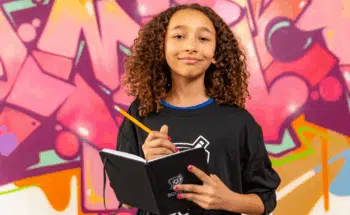

Since that moment, Boyde has continued to take DC SCORES seriously. In fact, DC SCORES has become her passion, first as a poet-athlete, then as a participant in DC SCORES’ elite poetry program, Youth W.O.R.D., and most recently as a Program Coordinator on the DC SCORES staff.

“It really feels like there is no other job I could have,” she says of the latest chapter of her time with the nonprofit. “I made my whole life SCORES.”

A Passion for Sports

Boyde grew up in the Brookland neighborhood of Washington, DC. Her family lived next to a busy apartment complex, and the volume of traffic and strangers on the street meant her father wouldn’t allow his three daughters to play outside on their own.

“It was a lot of going to parks, going to fields, going to basketball courts, and playing soccer and basketball with him. That was my childhood,” she recalls.

Boyde was raised by her father and grandmother in Brookland in Northeast DC.

Through these trips to the park, Boyde developed a love for sports. So, when she arrived for elementary school at Brookland Education Campus, she was excited about the prospect of playing soccer for DC SCORES. There was just one problem: she wasn’t old enough to join the team.

“I would go to my sister’s poetry slams, I would go to her games, I would go to her practices, and I was straight-up jealous,” Boyde remembers. The next year, she resolved to do something about it. “I threw a whole temper tantrum,” Boyde remembers. “I said, ‘I’m joining.’” She was on the team the next week.

She threw herself into the program, attending every game she could and showing up for every writing practice. At the former, she found a mentor to look up to in the form of her poetry coach. “I loved this lady,” Boyde says. “She had tattoos and piercings, she wore a beanie every day. She just looked so cool and I just wanted to be like her when I grew up!”

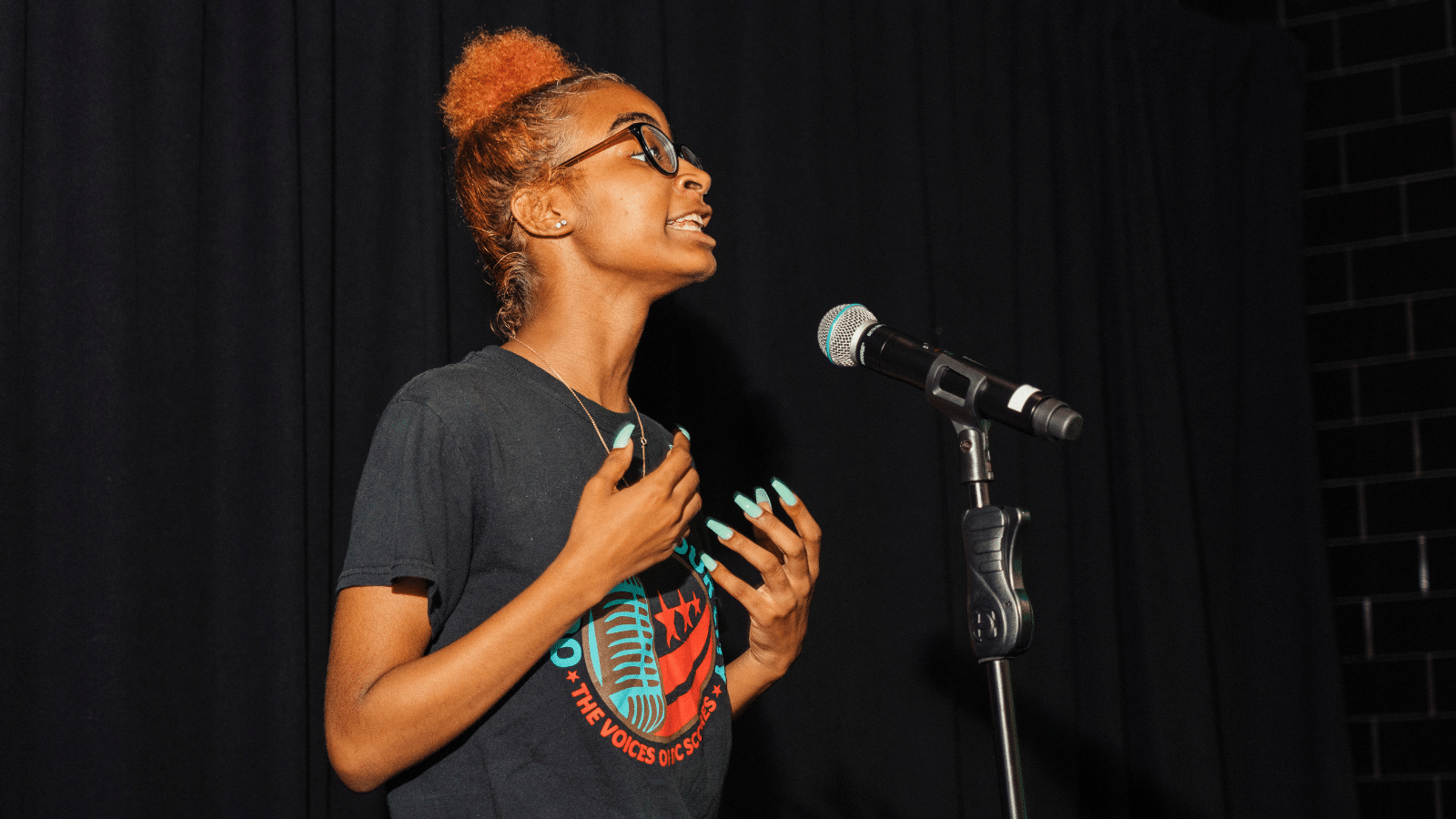

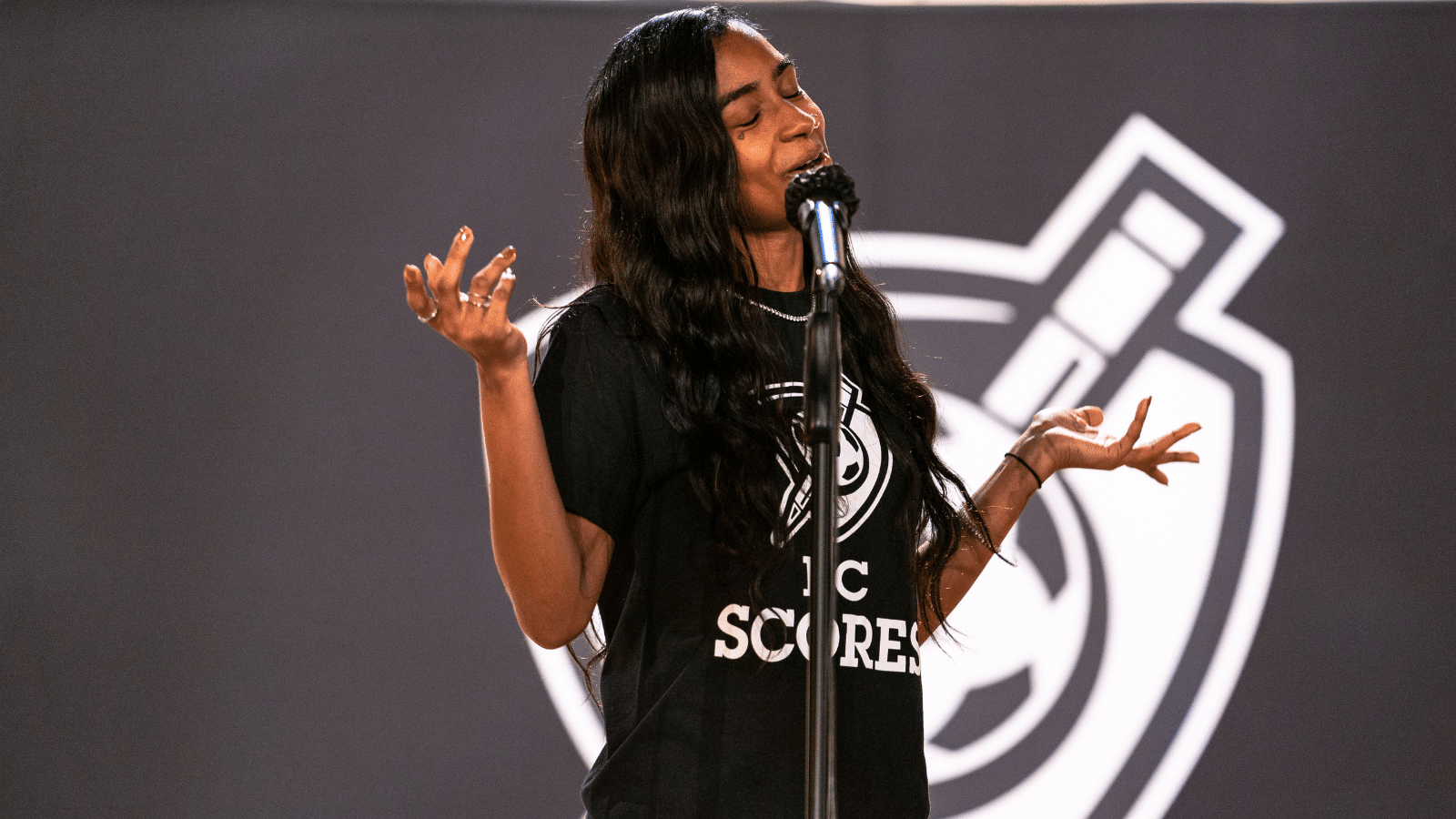

Boyde performs at the DC SCORES fundraiser gala One Night One Goal in 2019.

Power in Performance

Today, Boyde is following in her coach’s footsteps and inspiring DC SCORES poet-athletes through writing and performance. In her Program Coordinator role, she serves as the staff liaison to a number of DC SCORES schools and also helps to develop the organization’s poetry curriculum and events.

Her favorite part of her job is working with students, especially those from Wards 7 and 8. “Those are the kids that I always relate to the most,” she says. “I can talk to them.”

The wards have the highest proportion of Black residents in DC and they are also the poorest. That context, Boyde says, makes it especially important to approach students in a way that puts them at ease and helps them get the most out of their DC SCORES experience.

“I never walk in and try to be bigger than them,” Boyde notes. “That’s where a lot of people make a mistake.” Boyde also makes sure students know that their writing and self-expression are valued, which is critical when so many Black American children experience language-based racism. “I tell them, ‘I promise you, whatever you write, it’s good and can be shared,’” she explains. “A lot of kids respond to that.”

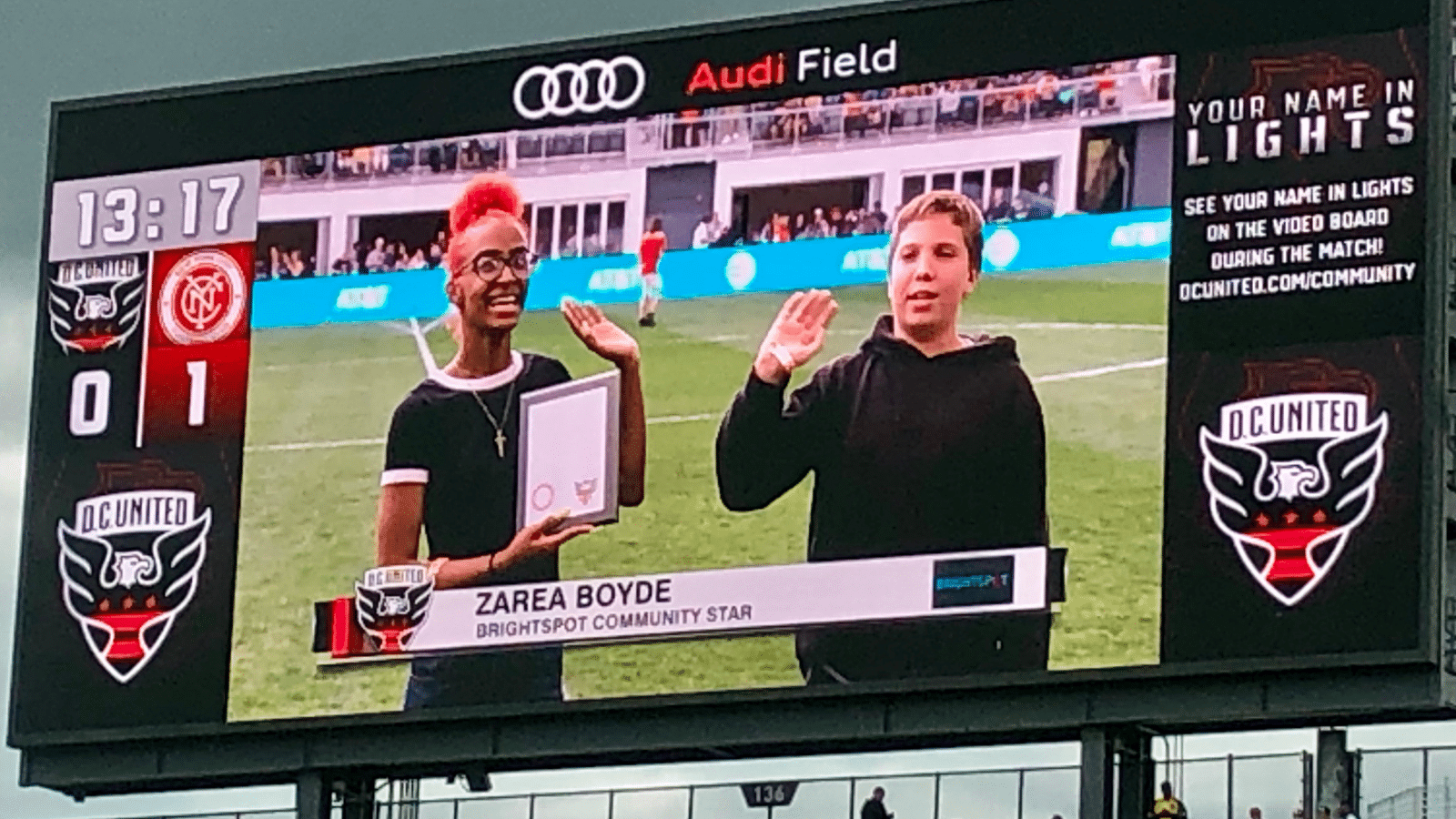

In April 2019, Boyde won the D.C. United Brightspot Community Star Award for her work with DC SCORES. She received the award at half-time during a D.C. United vs New York City FC game at Audi Field.

This work is personal for Boyde, who found her own power and agency through spoken word. Boyde has performed in front of audiences at Audi Field and the International Spy Museum. At many of these big-stage events, Zarea is often the youngest person in the space and one of just a handful of Black women. But, when she performs, everyone listens.

“It’s always been very important for me to able to walk in a room, look people in the eye, and make them understand that I’m a very important person,” she stresses.

“What We Do Is Big”

Boyde’s sees her work as activism: she tackles issues including Black Lives Matter and feminism in her work. “Poetry is my foundation,” she continues. “I really think I would never have been able to talk the way that I do, or advocate for myself and others, if I didn’t do poetry.”

She credits her father and grandmother, the two people who raised her, with helping her to develop the confidence it takes to address these topics from the stage. “My dad had a hard upbringing but became a successful music producer,” she shares. “He’s a big example in my life. And my grandma taught me a lot about being a good person, being patient, and being a humanitarian.”

Boyde performs as a special guest at the 2022 Middle School Poetry Slam at Cardozo Education Campus.

While Boyde often encourages her students to follow her lead and address serious issues that impact their lives in their poetry, she also says that DC SCORES provides an important space for kids to have fun. In fact, her favorite DC SCORES memory is of a water fight she had with her students while serving as a DC SCORES summer camp counselor. “It didn’t even last that long,” she says, “but the kids went insane. Yeah, that was fun.”

As someone who grew up in the program, Boyde knows how important these moments of joy are for DC SCORES poet-athletes. “What we do is big,” she explains. “‘Cause most of these kids, they’re not kids outside of practice. They walk themselves home, they feed their selves, they put their selves to bed, they get their selves up for school the next morning. That’s the life for most of these kids.”

She continues, “The two hours that we give them at practice, those extra two hours to be a kid, that means so much to them.”